Table of contents

- Determine where to cache data.

- Determine the write vs read frequency of your system or component.

- Determine what data should be strongly persisted.

- Determine what data should be cached on the server vs the client.

- Determine what data is safe to be cached.

- Determine the appropriate caching strategies and trade-offs.

- Determine the appropriate cache eviction policy.

- Consider data consistency between the cache and the database.

- Ensure the cache has redundancy and is not a SPOF itself.

- Consider seeding a small cache to improve performance.

- Consider over-provisioning the cache by a percent to provide a buffer.

- Consider data locality optimisations for cache-friendly applications.

Caches

🙃 The joke goes that whenever you’re faced with a distributed system problem, the answer is either a cache or a queue.

Determine where to cache data.

- Content Delivery Network (CDN)

- Application instances, e.g. local caches

- Databases, e.g inline caches like DynamoDB Accelerator

Determine the write vs read frequency of your system or component.

Highly dynamic data becomes stale very quickly. A good balance is to bundle the static and infrequently changing data for caching and compute the rest on-the-fly.

- Cache data that is read frequently but modified infrequently

- Cache data that is immutable

- Cache data that is expensive to compute

Determine what data should be strongly persisted.

And what is acceptable to be lost and recreated.

- Persist critical and auditable data on disk, e.g. in a database or files

- Persist data that you can afford to re-create in a memory cache

Determine what data should be cached on the server vs the client.

Remember you can’t directly force some types of clients (e.g mobile) to update their cache.

Determine what data is safe to be cached.

- Ensure that sensitive data is not cached, e.g. credit card information, passwords etc.

- Ensure the security of cached data.

- Ensure the privacy of the data in the cache, e.g. encrypted at rest with symmetric or asymmetric cryptography.

- Ensure the privacy of the data as it flows between the cache and its clients, e.g. encryption in transit over

TCP/HTTPwithTLS. - Determine which identities (users, services) can access data in the cache.

- Determine which operations (read, write) these identities can perform on the cache

Determine the appropriate caching strategies and trade-offs.

- Read-through cache (load data lazily)

- Write-through cache (add data to cache when data is written in the database)

- Write-back cache (only the cache gets updated and later in the database)

Determine the appropriate cache eviction policy.

Consider the expiration period carefully. If it’s too short, the cached objects will expire too soon and the cache benefits will be reduced. If it’s too long, you risk using stale data.

- FIFO (First-In First-Out)

- LRU (Least Recently Used)

- LFU (Least Frequently Updated)

Consider data consistency between the cache and the database.

A company had an incident once. An out-of-date database follower was promoted as a leader. The leader lagged behind the old leader’s auto-increment primary keys, meaning that some keys were re-assigned. These primary keys were also used in cache. The result: private data disclosed to the wrong users.

Ensure the cache has redundancy and is not a SPOF itself.

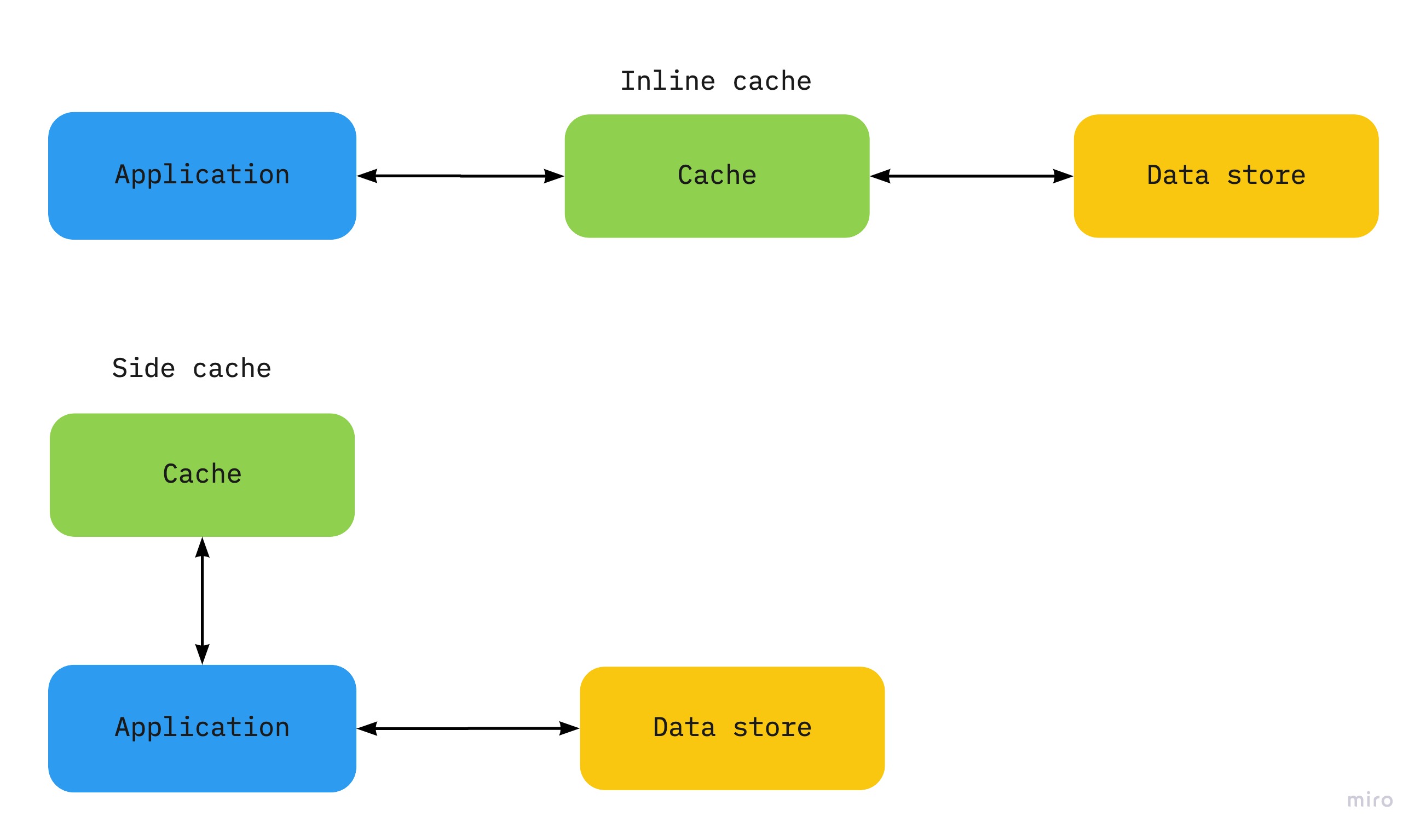

Inline vs side cache

|

|---|

| Inline vs side-cache |

An inline cache (read-through or write-through) embeds cache management into the main data access API, making cache management an implementation detail of that API, e.g. DynamoDB Accelerator (DAX), HTTP caching local or with an external service like Varnish or a CDN.

A side cache is a generic object store like Elasticache or libraries like Ehcache. With a cache-aside pattern, the application code maintains the cache using a caching strategy like read-through and write-through.

Trade-offs between an inline and a side cache

- A side-cache adds complexity because the application has to manage the lifetime of cached data while an inline cache pulls this logic out of the application code.

- An inline cache is more efficient for static data because it can be pre-warmed and configured with a policy that prevents data from expiring.

- A side-cache has more control over eviction algorithms and whether to apply the policy globally or not. For example if a cached item is very expensive to retrieve from the database, it could be better kept cached for longer at the detriment of other more frequently access but less expensive items.

- A side-cache offers more high-availability than an inline cache because it usually has a fail-over to a secondary cache in case the primary fails.

- Use an inline cache when available

- Use a side cache for more control over evicting data and better availability

Consider seeding a small cache to improve performance.

Pre-populating a small cache can improve performance and and minimise “cold-start”.

- Benchmark seeding with on-demand performance

- Seed with static user data, e.g. user profiles for frequent customers

Consider over-provisioning the cache by a percent to provide a buffer.

Consider data locality optimisations for cache-friendly applications.

Local vs shared cache

A local (on-box) cache is an in-memory cache held locally on the machine running an instance of an application/service, e.g. a hash table in memory.

A shared (external) cache is a separate service (or a cluster) that caches data independently of any application instance, e.g. Elasticache (Memcached, Redis).

Trade-offs between a local and shared cache:

- A local cache is quicker to access because of spatial locality (on the same machine)

- A local cache is limited by the amount of memory on the host while a shared cache can partition data across clusters of servers, hence more scalable.

- With a local cache, instances of the same application have their own copy of the data and it’s much harder to keep it consistent while some shared caches offer some help like read-repair and anti-entropy background processes.

The recommendation is to use a local private cache together with a shared cache.

Avoid making critical parts of the system too reliant on the shared cache. If the shared cache fails, the system shouldn’t become unresponsive or fail waiting for the cache service to resume.

This can be done by making the system fall back to the database and continue to function.

However, this also creates a scalability issue known as The Thundering Herd: all the running instances get a cache miss because the cache is down and hit the database at the same time. The more expensive the query, the bigger the impact on the database, for example, retrieving the profile of a social media influencer who is followed by millions of users.

The local cache can act like a buffer. When the application retrieves an item, if first checks in its local cache, then the shared cache then the database. The local cache is populated either with the data in the shared cache or with the one from the database, if the shared cache is unavailable. This approach is not problem-free either, because the local cache can easily become too stale compared to the shared cache.

- Consider temporal locality optimisations e.g. minimise cache miss in inner loops

- Consider spatial locality optimisations e.g. local vs shared cache, arrays vs linked-lists

- Read industry papers for optimisation ideas, e.g. Scaling Memcache at Facebook

- Run performance tests e.g. load a few GB of data in your cache and add a CPU hogging process in a some nodes, simulate slow/dropped network traffic etc.